Joseph A. Rose vs. Dr. Brooks D. Simpson:

What Really Happened on Orchard Knob and at Missionary Ridge?

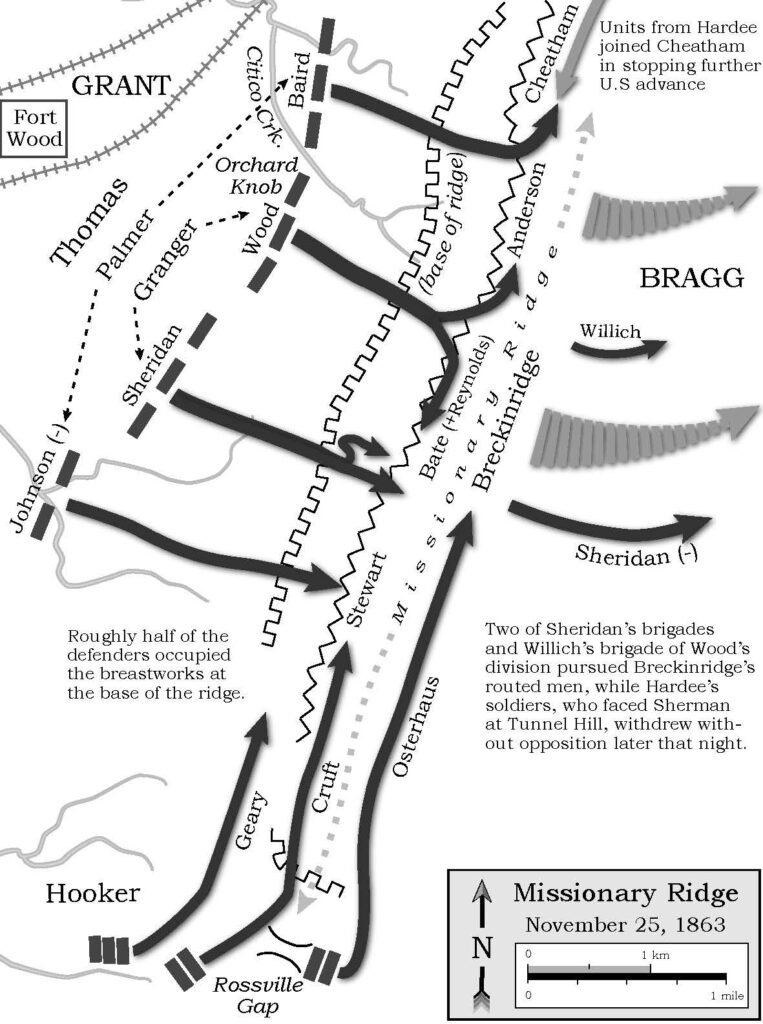

One of the Civil War’s most intriguing controversies concerns the “miraculous” charge up Missionary Ridge during the Battle of Chattanooga on November 25, 1863 and whether Major-General Ulysses S. Grant intended the soldiers to ascend, as he claimed. The Confederate defenders dug in at the bottom of the ridge, the top, and in between equaled if not outnumbered Major-General George H. Thomas’ assaulting troops from the Union Army of the Cumberland. Rebel artillery lined the crest, which rose over 300 feet at a roughly 45˚ angle. Many viewers thought this position invulnerable from in front. After the completely successful—yet wholly unexpected—assault by the soldiers up the ridge, overall commander Grant quickly claimed that this was his plan. Everyone did agree that he had ordered Thomas’ men to expel those Confederates in the rifle-pits at the base of the ridge, after Major-General William Sherman’s main thrust on the Union left had been sharply repulsed. But many disputed that Grant had intended the ascent, however, aware that he only desired a demonstration, and credited the courageous soldiers for taking matters into their own hands.

Noted historian David A. Powell, in The Impulse of Victory: Ulysses S. Grant at Chattanooga, didn’t choose one explanation over the other. He determined that the “two most useful analyses of all these competing accounts” were Dr. Brooks D. Simpson’s book chapter titled “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” and my analysis in Grant Under Fire: an Exposé of Generalship and Character in the American Civil War.[1] They are probably the most detailed treatments—despite being diametrically opposed—of this military episode.

Dr. Simpson, General Grant’s most renowned and prolific defender, concurs with that general and with his other biographers that Grant planned this ascent of the ridge, only “the men took things into their own hands and anticipated Grant’s next step.”[2] Simpson goes so far as to contend that actual orders to this effect had been promulgated. If true, this would establish Grant as a military genius, for daring an assault on a seemingly “impregnable” position and gloriously succeeding. The battle’s most eminent historians—James McDonough, Peter Cozzens, and Wiley Sword—reject this thesis.[3] These three emphasized how this was a mere demonstration, proposed to take the pressure off of Grant’s friend and protégé Sherman, with nothing further planned. They credited the subordinate officers and

the common soldiers who, finding themselves in a dangerously untenable situation, surprisingly climbed up the steep incline and drove the Confederates off the crest, albeit taking substantial casualties while doing so. Sword contended that Grant badly blundered by leaving General Thomas’ soldiers in a death trap from small-arms and artillery fire from atop the ridge and without further instructions. Serendipitously, the indefensible position, the rebels fleeing the initial advance, and the Union soldiers’ esprit de corps prompted an audacious upward surge. In this scenario, Grant not only showed grave tactical foolishness, he lied about his true intentions in both his official report and his Personal Memoirs. Disliking the former commander of the Army of the Potomac, he also downplayed Joseph Hooker’s simultaneous achievement in pushing the Confederates north along the ridge on the Union right.

Simpson started his hypothesis rather inconclusively: “Given what we know, the evidence leans toward the explanation Grant gave at the time to Meigs: that after Thomas’s men took the rifle pits, they were to re-form and await an order to carry the crest.” But this initial leaning immediately turned into positive declarations of Grant’s “overall intent” to carry the ridge using Thomas’ Army of the Cumberland.[4] How did Simpson treat the evidence in reaching such a conclusion, which conflicted with the vast majority of the informants who were there?

The most significant source Simpson presents in favor of his thesis is the rather unreliable Ulysses S. Grant himself. His draft after-battle report falsely claimed that “the enemy [was] weakening his center.” By doing so, Grant invented a reason for advancing Thomas’ men, while still crediting his friend Sherman for confronting an “enemy mass[ed] heavily against him.” After writing about the ascent’s commencement, he (or someone) crossed out the phrase “without orders from me,” even though Grant admitted that was true. As opposed to his assertion that Hooker’s “approach should be the signal for storming the ridge in the Center with strong columns,” Grant had shown little interest in Hooker’s doings, focusing on the opposite flank and Sherman, who remained the focus of Grant’s operations. Besides that, Grant initially forgot Johnson’s division in the charge; grossly distorted the battle plan; and almost certainly did not order such explicit dispositions for Thomas’ troops or expect Hooker’s to assume a trident formation. In other errors, the center did not do “on the 23d what was intended for the 24th” and the ascent on the 25th was not made “from right to left.”[5] In describing the orders given to Thomas in his final version, Grant inserted that when the rifle-pits at the base had been carried he was “to reform his lines on the rifle-pits with a view to carrying the top of the ridge.”[6] Simpson, oddly enough, repeatedly denied that Grant ordered the men to reform (“… that after Thomas’s men took the rifle pits, they were to re-form and await an order to carry the crest. Grant never issued that particular order, but that was the overall intent of the operation” and “… the fact that the only order actually issued concerned taking the rifle pits at the base of the ridge”) even though it is one of the few pieces of evidence favoring his thesis.[7] No significant participant, moreover, heard such orders or corroborated Grant’s claim of intent.

Quartermaster-General of the U.S. Army Montgomery Meigs, Simpson’s other major witness, observed the assault from Orchard Knob. Two days previously, Brigadier-General Thomas Wood’s division had seized this hundred-foot high hill a mile in front of Missionary Ridge, and it now served as the Union command post. In his journal entry for the 25th, Meigs jotted down Grant’s post hoc claim that he had intended to capture the ridge (“Grant said it was contrary to his orders, it was not his plan—he meant to form the lines and then prepare and launch columns of assault”). Meigs did not offer his own confirmation of Grant’s contention. Merely repeating what he was told did not make Meigs a believer of Grant’s claim. Simpson optimistically presumed that the Quartermaster-General’s journal “helps resolve one of the puzzling events of the battle, namely what Grant intended to do when he directed Thomas to order his four divisions forward.” It does not do this. In fact, Meigs omitted Grant’s claim of intent in his detailed description of the battle dispatched to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton the very next day, excluding an important piece of information if it were true. Simpson twice implied that Grant mentioned his intent to Meigs at the time of the charge. That may or may not be true, but the journal entry was not written by Meigs until well after the ridge had been taken—most likely in the evening back in Chattanooga upon going to Grant’s headquarters to hear the result where he learned the battle’s details for inclusion in his journal.[8]

After commenting on Meigs’ journal, Simpson quoted a portion of a November 26th telegram to Secretary Stanton from Assistant Secretary of War Charles A. Dana, another observer on Orchard Knob: “the ‘orders were to carry the rifle-pits along the base of the ridge and capture their occupants, but when this was accomplished the unaccountable spirit of the troops bore them bodily up’ the ridge,” which did nothing to advance his thesis.[9] Inconceivably, Simpson omitted Dana’s superlatively crucial sentence immediately prior to this: “Neither Grant nor Thomas intended it.” This telegram had followed a stream of informative communiqués that Dana sent to the War Department as Grant’s liaison. Dana, Grant’s friend and staunch supporter, was keenly aware of what transpired. Nothing impeached his account, except that Dana would occasionally twist facts … in Grant’s interest.[10] Beyond Grant’s own writing, very little evidence from those on Orchard Knob exists to question, much less refute, Dana’s unqualified denial of Grant’s intent, while a wealth of accounts collectively contradicts Simpson’s argument that Grant meant for the troops to ascend.

George Thomas’ circumspect post-battle report described how the soldiers pursued the retreating Confederates up the ridge, “apparently inspired by the impulse of victory,” while “the original plan of operations was somewhat modified to meet and take the best advantage of emergencies, which necessitated material modifications of that plan.”[11] More tellingly, the report of his corps commander, Major-General Gordon Granger, specifically noted that “I was ordered to make a demonstration upon the works of the enemy directly in my front, at the base of Mission Ridge,” and only that. “My orders had now been fully and successfully carried out, but not enough had been done to satisfy the brave troops, …” Granger continued, “they dashed over the breastworks, through the rifle-pits, and started up the ridge.”[12] Later, he wrote his old commander Rosecrans: “… my troops made the most gallant charge yet on record, won all the glory + captured all the trophies which Grant intended for Sherman, while the latter was three times shamefully repulsed. And what is more I gave the order + took the responsibility of making the Charge altho Grant Claims in his report that he did it. It is untrue. If I had been repulsed or defeated he would have arrested me for assaulting without orders + uselessly slaughtering my men.”[13] Granger had astutely instructed his two divisions to keep going up the ridge soon after the ascent began.[14]

Thomas Wood, one of Granger’s two division commanders in the assault, noted that the ascent was “positively prohibited” by Grant.[15] Simpson’s article, to counter such evidence, speciously maintained that Wood’s impassioned refutation of Grant’s claims from 1876 to 1896 was “fueled by anger against Grant.”[16] Not only did Wood show no anger in referring to “the illustrious military services of Gen. Grant,” he initially expressed his assessment in an after-battle report: “To lessen the opposition General Sherman was encountering, it was determined that a movement should be made against the rebel center. I was ordered to advance and carry the enemy’s intrenchments at the base of Mission Ridge and hold them. … Our orders carried us no farther. We had been instructed to carry the line of intrenchments at the base of the ridge and there halt.”[17] Wood expanded on this afterward: Grant said, “‘If you and Sheridan advance your divisions to the foot of the Ridge, and there halt. I think it will menace Bragg’s forces so as to relieve Sherman.’ He repeated for us to halt at the foot of the Ridge, but not to attempt to go up the Ridge, because all councils antecedent to this considered Mission Ridge too strong in the center to make the attack with any hope of success. I speak with my own knowledge.”[18] Furthermore, Grant recalled that “Sheridan’s and Wood’s divisions had been lying under arms from early morning, ready to move the instant the signal was given. I now directed Thomas to order the charge at once,” with an asterisked remark, “In this order authority was given for the troops to reform after taking the first line of rifle-pits preparatory to carrying the ridge.”[19] Speaking directly to Wood on Orchard Knob after the delay, Grant remembered, “I spoke to General Wood, asking him why he did not charge as ordered an hour before. He replied very promptly that this was the first he had heard of it, but that he had been ready all day to move at a moment’s notice. I told him to make the charge at once.”[20] If Grant had any intention of ascending the ridge, he should have told Wood then and there. Instead, Wood had written Grant in 1885 that “I have no knowledge of your orders to Genl Thomas except as learned from you.”[21]

Simpson further alleged that “One of Wood’s own brigadiers, Brigadier-General August Willich, believed his orders were to take the crest.” But Willich actually reported that, “I understand since that the order was given to take only the rifle-pits at the ridge … I only understood the order to advance.”[22] Even though he was unsure at the time, Willich later declared that the ascent stood “contrary to the distinct orders of the Commander-in-chief,” thus contradicting Simspon’s contention.[23] Brigadier-General William Hazen, another brigade commander in Wood’s division, but present on Orchard Knob before the attack, declared that the rifle-pits at the base were the objective; Simpson agreed that Hazen asserted that “the orders were to stop at the rifle pits.”[24]

Granger’s other division commander in the charge was Major-General Philip Sheridan. Simpson repeated Bruce Catton’s baseless argument that Sheridan “suddenly realized that his orders were vague.”[25] Instead, Sheridan’s official report expressly noted how “the original order was to carry the first line of pits,” while his memoirs explicitly stated that the “assault on Missionary Ridge by Granger’s and Palmer’s corps was not premeditated by Grant, he directing only the line at its base to be carried.”[26] Sheridan had been concerned whether these orders were correct; as the rifle-pits at the base “seemed as though they would prove untenable after being carried, the doubt arose in my mind as to whether I had properly understood the original order.”[27] He sent back to Orchard Knob to confirm this. As Sheridan became and remained Grant’s protégé, his friend, and one of his favorite generals, any possible prejudice against Grant can be readily dismissed. Although Sheridan was off to the right of Orchard Knob, he was certainly in a position to ascertain the facts afterward. Granger’s Chief of Staff, Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Fullerton recollected after the war, “In Sheridan’s division the order was, ‘As soon as the signal is given, the whole line will advance, and you will take what is before you.’”[28] Simpson tried to make this seem ambiguous as to the intended objective. It was not. Fullerton had written immediately before: “This demonstration was to be made to relieve the pressure on Sherman. The only order given was to move forward and take the rifle-pits at the foot of the ridge.”[29]

To Sheridan’s right, Brigadier-General Richard Johnson’s division was merely ordered to conform with Sheridan’s movements.[30] As Sheridan had been instructed to stop at the base of the ridge, so was Johnson. Johnson’s corps commander, Major-General John M. Palmer, apparently left no record as to Grant’s intention, beyond noting how the men, “obeying a common impulse, made their way up the face of the mountain.” Palmer’s other division commander in the attack was Brigadier-General Absalom Baird. Grant’s instructions to Baird’s division confirmed his lack of intent. Thomas had ordered Joseph Hooker’s ten thousand-man force to descend from Lookout Mountain far on the Union right—where his “Battle above the Clouds” a day earlier had dissolved the Confederates’ left flank—and then pivot counter-clockwise from the south against the enemy’s new position on Missionary Ridge, along with the centre divisions of Johnson and Baird. Grant disrupted Thomas’ plan for some unknown reason, choosing to send Baird from Thomas’ right all the way to Sherman on the union left, with no idea of its return. Sherman, however, had not asked for and did not need any more soldiers. He serendipitously returned the division barely in time for Thomas’ advance on Missionary Ridge. This was prima facie evidence that Grant planned no full-scale assault, unless he somehow expected a much smaller force to succeed when officers thought taking the ridge was highly improbable even with a larger one. Grant speciously argued in his Personal Memoirs that Baird drew Confederate troops toward Sherman’s front, which “was what I wanted,” although that contradicted his repeatedly avowed purpose of succoring Sherman.[31]

Brigadier-General William F. (Baldy) Smith, whom Grant chose as a protégé during the Chattanooga campaign and put on staff as Chief Engineer, formulated the original plan of assault against the enemy’s positions. He also carried Grant’s attack order to Absalom Baird on the 25th, which only referred to the Confederate positions at the base of the ridge. When Baird asked what should he do after that, Smith responded, “I have given you the entire order in the exact words of General Grant.”[32] He should thus have been well aware of Grant’s intentions. Just two weeks after the battle, Smith informed West Point professor Dennis Hart Mahan that “the centre was ordered forward to take the rifle pits, at the base of the ridge … they moved steadily forward, took the lower rifle pits & the soldiers insisted so strenuously on assaulting the ridge, that the Division Commanders were powerless to stay them.”[33] He later summed up the affair: “Grant sent orders directly to the division commanders of the Army of the Cumberland to move forward and carry the rifle-pits in their front at the base of Missionary Ridge. … The assault on the center before either flank was turned was never seriously contemplated, and was made without plan, without orders, and as above stated”[34] Simpson blithely dismissed evidence given by Smith, as he purportedly “had been upset with Grant for some two decades.”[35]

The belated arrival of Baird’s division from its futile march to Sherman offered further confirmation of Grant’s lack of intent. Baird reported that immediately before the advance, he “had just completed the establishment of my line, and was upon the left of it, when a staff officer from Major-General Thomas brought me verbal orders to move forward ….” An hour earlier, when Grant either suggested or directed an assault of the ridge, Baird’s division was not nearly in position to advance. Thomas’ messenger continued, “this was intended as preparatory to a general assault on the mountain, and that it was doubtless designed by the major-general commanding that I should take part in this movement, so that I would be following his wishes were I to push on to the summit.”[36] Simpson presented James A. Connolly’s description of how “Baird told him to relay an order to brigade commander Edward Phelps, calling on Phelps to advance ‘to storm the heights and carry the Ridge if possible,’” just before the signal to advance about 3:30 P.M.[37] This indicates that Baird’s division did not receive any instructions based on Grant’s first mention of an attack an hour before. It conflicts with Grant’s order which “Baldy” Smith had taken to Baird, although it doesn’t differ from the sentiment provided by Thomas’ messenger. Curiously, Connolly told how the men “climbed up the mountain,” after reaching the foot, “without further orders.”[38]

The evidence further shows that Grant initially expected the advance on Missionary Ridge to be undertaken by only Wood and Sheridan. If he did intend their ascent, then Grant illogically expected that just two divisions could expel a force about twice their size from the immensely formidable position on and before the ridge. Years later, Joseph Fullerton quoted Grant on his real intent: “I wish Granger’s men to make a demonstration on the rifle-pits at the bottom of the Ridge. I must do something to help out Sherman.”[39] Grant’s Memoirs stated: “But Sherman’s condition was getting so critical that the assault for his relief could not be delayed any longer.”[40] The Memoirs repeatedly referred to Sheridan’s and Wood’s divisions before and during the assault, only mentioning Baird’s toward the end and omitting Johnson’s altogether. Grant’s phrasing, “Granger, commander of the corps making the assault,” ignored both Baird and Johnson, who reported to the other corps commander, Palmer.[41] Additionally, Wood recalled that, “It is my impression that Gen. Grant contemplated originally moving only Sheridan’s and my division against the Confederate intrenchments at the base of the ridge, and that Baird’s division on my left, and Johnson’s division on Sheridan’s right—both of the Fourteenth Corps were included in the movement at the suggestion of Gen. Thomas.”[42] Wood later explained that “Johnson was at the right of Sheridan, and on my left was Baird, added on the suggestion of General Thomas to make the menace of the center more decided and pronounced, if we were successful in carrying the rifle-pits at the foot of the Ridge.”[43]

Little evidence exists of Grant’s supposed desire to reform the divisions into “columns of assault” after reaching the base of the ridge. It would have been a tactically stupid proposition, in any event, as the men would be forced to leave the limited protection of the captured rifle-pits and form and remain in massed formations until further directions might arrive from Orchard Knob. During this time they would be sitting ducks for Confederate artillery and small-arms fire. Grant’s subordinates on Orchard Knob and the commanders undertaking the assault mentioned no such orders. As Grant had not informed these subordinates beforehand, riders would have had to go out—to the four division and eleven brigade commanders—to coordinate any attack without undue delay.

Charles Dana and James H. Wilson’s 1868 biography “would have pleased Grant and Sherman,” according to Simpson, even though the ascent stemmed from “‘one of those wild and unaccountable impulses originating in the native sagacity of men and officer alike,’ the men continued up the slope with the crest as their objective.”[44] That hardly illustrated any special intention on Grant’s part. Simpson argued that Wilson’s later description of the charge in an autobiography and in his biography of Grant’s chief-of-staff John Rawlins “added nothing substantial to what was already known about the orders themselves, as he was not privy to the content or wording of the orders transmitted down Thomas’s chain of command.”[45] But Wilson was the individual who carried Thomas’ attack orders to Baird, so he was privy, and Wilson was friends with Rawlins and in a position on Orchard Knob to ascertain what was happening. Wilson later stated that “I was standing by General Grant when he ordered Thomas to advance, and personally know that there was nothing in his language which in the slightest degree indicated that he wanted anything more than the line of rifle pits at the foot of the hill carried.”[46]

Likewise on Orchard Knob, Captain Lyman Bridges commanded the Union battery that signaled the initial assault with six cannon-shots. He wrote that the troops “were ordered to press forward and carry the first line of rifle-pits of the enemy at the foot of Missionary Ridge and await orders.” “Upon arriving at this line it was found impossible to remain there, on account of the range of the enemy’s guns on the Ridge covering this line. It was necessary either to advance up the Ridge under cover of benches, logs, trees, etc., or fall back to the line of works from which they had advanced.” Bridges continued his account: “Standing upon Orchard Knob, I heard Grant ask Thomas by whose orders those troops were going up Missionary Ridge. After a moment’s delay Thomas replied: ‘Probably by their own orders.’ Grant’s reply was ‘Somebody will suffer if they do not stay there.’”[47]

Joseph Fullerton’s account featured Grant “angrily” asking Thomas, “who ordered those men up the ridge?” and threatening whoever was responsible if they did not succeed (“something to the effect that somebody would suffer if it did not turn out well”).[48] Grant’s anger, questioning, and threat all do much to contradict his later claim of intent. Grant asserted in his Memoirs that “It is always, however, in order to follow a retreating foe, unless stopped or otherwise directed,” and he should have been ecstatic—not angry—to see it happening here. Supporting Fullerton’s description, reporter William F.G. Shanks and Wood confirmed Grant’s anger; Sheridan (according to Fullerton), Granger, Wood, Bridges, and Shanks referred to the questioning; and Granger, Wood, Bridges, and Shanks corroborated the threats.[49] In addition, Fullerton stated that Grant “gave no further orders” while watching the ascent, whereas any commander intending such a movement should have sent out directions for the troops to continue to the crest.[50] Grant’s friend and Thomas’ chief-of-staff, Joseph Reynolds, had an otherwise-quiet Grant watch the troops successfully assault the ridge, “until it was evident that the whole army was assaulting successfully what had seemed to be an impregnable position,” and then Grant merely queried Thomas: “Are battles chance?”[51] Grant’s reactions reveal the exact opposite of an intent to ascend.

Simpson utilized the recollections of Grant’s pet correspondent, Sylvanus Cadwallader—a friend and a de facto member of Grant’s staff—as confirmation of a steadfast Grant and a timid Thomas on Orchard Knob watching the troops scale the ridge. Curiously, in his introduction to Cadwallader’s volume of recollections, Three Years with Grant, Dr. Simpson extolled the book’s evidence of Grant’s intent to ascend Missionary Ridge.[52] This testimony disappeared, surprisingly, from his later book chapter. Maybe Simpson discovered the reporter’s contemporary Chicago Times article, composed the very evening of the 25th. It distinctly affirmed that “Division commanders were especially instructed to make no attempt to ascend the face of the ridge.”[53] Not only is this positive and very contemporary evidence of Grant’s lack of intent, it demonstrates how his supporters would distort the truth—once they learned what story they were supposed to tell. But Cadwallader had left Chattanooga at ten o’clock that night. His Three Years with Grant includes unsubtle disparagement of Thomas (“never distinguished himself unqualifiedly in any independent command”) and Grant’s version of the supposed orders (“The original intention had been to call a halt of our troops in these trenches [the rifle pits at the base of Missionary Ridge] until the whole line could be reformed, and directions given for the perilous ascent before them”).[54]

Reporter John E.P. Doyle was on Orchard Knob and had written that the sudden advance of Thomas’ Army upon the Missionary Ridge “was a surprise alike to generals Grant, Thomas and Wood.” Their reactions were “very positive proof that a charge upon the stronghold of Bragg at that time was not a part of either Grant’s or Thomas programme.”[55] Another correspondent, Charles D. Brigham, wrote that, “I do not know that any one so proclaimed, nevertheless everybody seemed to understand, that Thomas’s force only waited for the order to assault Missionary Ridge,” and that “When the rifle-pits were carried, the men were to halt for further orders. There was no halt. Our forces kept going … contrary to the plan of battle.” He did believe, though, that Grant intended an ascent at some point.[56]

Other incidents helped to prove the lack of Grant’s intent to ascend the ridge. In a footnote, Simpson explained: “Although Grant’s kinsman, William Wrenshall Smith, penned a journal of his experiences during the campaign, his observations do not significantly bear on this discussion.”[57] But they do. Smith went with Grant and others off Orchard Knob for a lunch break after 2:00 P.M. A fair estimate would be that lunch, “smoking and talking pleasantly for half an hour more,” and returning took about an hour in total.[58] This is consistent with Grant suggesting or ordering Thomas to advance to the base of the ridge and then leaving for lunch, before returning around half-past three to find that Thomas’ advance to the base of the ridge had not yet occurred. Smith’s timing of Grant’s positive order to assault corresponds with other accounts.[59] According to his Personal Memoirs, Grant “watched eagerly to see the effect, and became impatient at last that there was no indication of any charge being made.” His finding that nothing had happened during the hour after the first “order,” as he called it, corresponds with his leaving for a one-hour lunch after giving it. If Grant had been on Orchard Knob for an hour without noticing that nothing had taken place to initiate an advance, it would not speak well for his powers of observation. Either way, the absence of the six-cannon signal starting the advance should have clued him in that his suggestion or order was not being followed. Much worse, leaving for an hour after sending men to a dangerously untenable position with no further directions would have been an abdication of his responsibility as a commander. If Grant were intending an ascent upon his instructions—but unnecessarily absent and thus incapable of giving them—it would have been a demonstration of utter military incompetence. It took Thomas’ soldiers less than thirty minutes to reach the base of the ridge, once they started.

What Quartermaster-General Meigs’ journal entry really revealed was Grant’s immediate endeavor to rewrite the battle’s history. Grant had given Sherman the starring role—in which the latter, commanding Grant’s old Army of the Tennessee, failed utterly—but told his subordinate that very evening that he could feel pride “in taking, first, so much of the same range of hills, and then in attracting the attention of so many of the enemy as to make Thomas’ part certain of success.”[60] An unanticipated and close-run victory now became a certain and easy deed, while Grant transmogrified Sherman’s failure into a positive achievement. At 3 P.M. that day, Sherman insisted that the “orders were that I should get as many as possible of the enemy in front of me and God knows that I have enough,” according to his staff engineer, Captain William Le Baron Jenney.[61] This was a lie, as that was not the plan.

Despite a vaunted reputation for honesty, Ulysses S. Grant was often untruthful during and after the war. The day after being chased off the battlefield at Belmont, Missouri, in his first engagement, Grant boasted to Brigadier-General Charles F. Smith that the “victory was complete” and to his father that “the victory was most complete.”[62] Grant told one of the war’s most audacious falsehoods less than three weeks after the battle of Shiloh: “As to the talk of a surprise here, nothing could be more false. If the enemy had sent us word when and where they would attack us, we could not have been better prepared.”[63] Instead, his (and Sherman’s) utter neglect of intelligence duties and proper preparations left the Union army almost completely unready for the Confederate attack. Both generals denied to the end of their lives that there was an enormous surprise for which they bore responsibility. In his Personal Memoirs, Grant strayed far from the truth by contending that his “first orders for the battle of Chattanooga” called for Hooker to get across the end of Missionary near Rossville when “the Army of the Cumberland was to assault in the centre.”[64] Instead, Thomas was to send two division of Cumberlanders left toward Sherman, to parallel his movement along the ridge, while no such proposal existed for Hooker. Rossville was behind the enemy lines when the plans were compiled, and anyway the apparently insurmountable Lookout Mountain prevented his reaching it. These can only be deemed obvious fabrications by Grant.

Grant would have deserved great credit if he actually intended such a bold maneuver that won the battle. His false claim of intending the ascent attempted to secure the laurels, while having the further benefit of covering up his fatal foolishness of having the men waiting at the base of an enemy-filled ridge. Had any other participants (besides Sherman) a motive to provide an inaccurate account? Officers in the Army of the Cumberland had no reason to lie about Grant’s intent, as the courageous ascent by the common soldiers and their immediate superiors did not depend on it in any way. William Hazen reported after the battle, his “command had executed its orders, and to remain there till new ones could be sent would be destruction; to fall back would not only be so, but would entail disgrace.”[65] Wood’s other brigade commanders, August Willich (“It was evident to every one that to stay in this position would be certain destruction and final defeat; every soldier felt the necessity of saving the day and the campaign by conquering, and every one saw instinctively that the only place of safety was in the enemy’s works on the crest of the ridge”) and Brigadier-General Samuel Beatty (“The fire of the enemy was so hot here, and enfiladed us so completely, that Colonel Knefler, commanding the two regiments, was not ordered to halt, and pushed on up the hill”) reported similarly.[66] The officers’ official reports would have indeed been a peculiar place to put unfounded criticisms of Grant, their commander. Most tellingly, Sylvanus Cadwallader and Charles Dana would not have intentionally diminished their friend’s reputation when writing that day and the day after, respectively, of Grant’s absence of intent.

There are further issues with Simpson’s article. He did his best to demean George Thomas, implying timidity, while Granger “comes off as something of a fool.”[67] Simpson wrote: “Nor do we know what was on [Thomas’] mind when he saw his men make their way up the crest.” Yet, Thomas twice sent orders to Wood to keep going up, stating that Wood would be supported. His subordinate, corps commander Granger, urged Wood’s and Sheridan’s divisions to continue up the ridge. In reviewing the historiography concerning this incident, Simpson routinely maligned those historians and Thomas’ biographers who reached a conclusion opposite to his own or who held a perspective critical of Grant (e.g., Thomas Van Horne, Donn Piatt, Richard O’Connor, Francis McKinney, Freeman Cleaves, Shelby Foote, Peter Cozzens, and Benson Bobrick) for “their infatuation,” “imaginative adventures,” “speculations,” “not above spinning a more vivid tale,” “not so careful,” “managed to overlook a great deal,” “neglect of more recent scholarly studies,” “imaginative renderings fueled by personal prejudices,” etc.[68] Conversely, Grant’s biographers, who often compiled their histories with little real criticism of their subject, escaped Simpson’s denigration. When William Sherman and Adam Badeau each manufactured plans of battle after the fact to match what actually happened, Simpson excused it as mere “rationalization.”[69] These were out-and-out falsehoods. Among the efforts to impeach accounts that refute his thesis, Simpson maintained that “Piatt was not present on Missionary Ridge, and as he gave no source for his conversation, one might well set aside his narrative,” yet he accepted Albert Richardson’s pro-Grant tale about whom the same can be said.[70] In fact, Simpson quoted Richardson’s dialogue on Thomas’ supposed expression of alarm about how the men “will be all cut to pieces,” even though the speaker had been identified in Richardson’s posthumous second edition as James H. Wilson.[71]

Simpson mistakenly wrote how “Grant then turned to Granger and asked if he had issued such an order.”[72] Fullerton’s writing clearly indicates that Thomas asked Granger the question, after being asked himself by Grant.[73] Simpson also supposed that William F.G. Shanks was an eyewitness of events on Orchard Knob, when that newspaperman had in fact stationed himself with Sherman miles away and apparently only returned to the centre riding his “by no means rapid beast” in time to see the Cumberlanders attack.[74] As with Cadwallader, Simpson apparently failed to notice how Shanks’ contemporary reporting conflicted with his later writings. In this case, Shanks’ 1899 news article reversed his own (and Simpson’s) characterization of an imperturbable Grant and a timid Thomas on Orchard Knob that day: “Gen. Grant, with some show of anger, addressing Gen. Thomas, asked, ‘Who ordered them to charge the ridge?’ ‘I guess,’ said the imperturbable Thomas, whose iron nerves nothing could shake, ‘they’re going up on their own orders,’ Gen. Grant muttered, ‘Somebody will suffer for this,’ and called to his orderly to bring his horse.”[75]

Simpson tried to diminish, if not dismiss, Wiley Sword’s scathing criticism of Grant’s instructions to halt at the rifle-pits (“It was a blueprint for disaster” and “Grant had made a poor tactical decision, which was impulsive and not very well thought out.”). Although Simpson alleged that “A check of the notes reveals that [Sword’s] account was built upon the recollections of Wood and Fullerton,” Sword’s footnotes for this incident include Granger’s contemporary after-battle report from the Official Records (“General Sherman was unable to make any progress in moving along the ridge during the day, as the enemy had massed in his front; therefore, in order to relieve him, I was ordered to make a demonstration upon the works of the enemy directly in my front, at the base of Mission Ridge”).[76]

Moreover, Simpson alleged that “no one recorded anyone raising the objection at the time that such an advance was suicidal,” even though Granger did so on November 23rd after Orchard Knob fell (“The enemy’s rifle-pits in front, 1,200 yards, very strong and filled with rebels. They cannot be carried without heavy loss”); Dana did so in a dispatch at 1 P.M. on the 25th (“In our front here rebel rifle-pits are fully manned, preventing Thomas gaining ridge”); and Sheridan thought so just before the attack (“… closely examining the first line of pits occupied by the enemy, which seemed as though they would prove untenable after being carried”).[77]

Simpson spent a great deal of effort detailing how Bruce Catton’s view of this episode evolved from one book to the next, yet he accepted Catton’s ultimate conclusion of Grant’s intention to ascend.[78] Suffice it to say that Catton got this generally correct in his earlier works, but switched to an inaccurate, pro-Grant scenario in his later two-volume biography of the general—just as he did with other controversies (e.g., Grant’s denying the surprise at Shiloh, his ordering the men to charge over an unexploded mine at the Crater, and his hectoring of Thomas at Nashville). Not only did Simpson follow Catton in asserting that Grant planned an ascent up the ridge, both authors contended that, “The storming of Missionary Ridge came under orders.”[79] It did not. The ascent was begun by the soldiers and lesser officers in Wood’s and then Sheridan’s divisions without any directive from above. This stands as a fine example of how Grant biographers concoct explanations in Grant’s favor as a matter of course.

Steven Woodworth, the editor of the book containing Dr. Simpson’s chapter, characterized “What Happened on Orchard Knob” as a “tour de force of historical investigation.”[80] Au contraire, that a scholarly article could contain so many factual mistakes and engage in such egregious argument is really quite astounding. Simpson’s undiscriminating acceptance of sources which support his version while rejecting those which do not would not be all that remarkable if the evidence were in his favor. As hardly anyone on Orchard Knob suggested that Grant intended the ascent, as opposed to the many who explicitly differed, Simpson demonstrated a blind and unjustified prejudice in favor of Grant.

Along with disproving Simpson and Grant’s other concurring biographers, analysis of this episode reveals how Grant gained undeserved credit—as happened at other times during the war (e.g., Shiloh)—for supposedly winning the battle despite a very checkered performance. He was afterward promoted to Lieutenant-General and general-in-chief. He advanced his friends and protégés (e.g., Sherman, Sheridan, Howard, Reynolds, Smith, and Wilson) even if they did little or worse, while maintaining or downgrading those who accomplished much more to secure the victory (e.g. Thomas, Hooker, and Granger). The events at Chattanooga finely displayed Grant’s poor tactical decision-making, negligence of responsibility, undue favoritism and unfairness, and considerable unreliability when writing official reports or personal memoirs. Grant Under Fire: an Exposé of Generalship and Character in the American Civil War comprehensively details these traits throughout Grant’s war-time career and after. A more complete account of the Battle of Chattanooga can be found on Pages 257–98. The first chapter can be read online at https://www.grantunderfire.com/introduction-to-grant-under-fire/.

[1] David Alan Powell, The Impulse of Victory: Ulysses S. Grant at Chattanooga (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2020); Steven E. Woodworth and Charles D. Grear, eds. The Chattanooga Campaign (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2012), Brooks D. Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 84–105; Grant Under Fire: an Exposé of Generalship and Character in the American Civil War. pp 289–98.

[2] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 87.

[3] Wiley Sword, Mountains Touched with Fire: Chattanooga Besieged, 1863 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997), 264–65; James L. McDonough, Chattanooga: A Death Grip on the Confederacy (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1984), 165; Peter Cozzens, The Shipwreck of Their Hopes: The Battles for Chattanooga (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 247–48, 260.

[4] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 100–1.

[5] PUSG 9:561–63.

[6] U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (hereafter OR) (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880–1901), 31:2:34–35.

[7] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 87–88, 100.

[8] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 98, 100.

[9] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 85.

[10] OR 31:2:68–69. On the 25th, Dana had correctly stated that “The day is decisively ours. Missionary Ridge has just been carried by a magnificent charge of Thomas’ troops, and rebels routed. Hooker has got in their rear.” He then contradicted himself the next day, falsely declaring that, “I find that I was mistaken in reporting in my dispatch of 4.30 p.m. that Hooker had got in the enemy’s rear. He was delayed in building a bridge across Chattanooga Creek, and only came up in time to occupy a part of the ridge on the extreme right.” Such anti-Hooker sentiment fit perfectly with Grant’s prejudices.

[11] OR 31:2:96–97.

[12] OR 31:2:132.

[13] Gordon Granger to William S. Rosecrans, June 6, 1864, William S. Rosecrans Papers, UCLA.

[14] Fullerton, J.S. “The Army of the Cumberland at Chattanooga,” Clarence C. Buel and Robert U. Johnson, eds., Battles and Leaders of the Civil War (hereafter Battles and Leaders) (New York: Century, 1887), 3:725.

[15] Thomas Wood to George B. Loucks, February 26, 1896, Filson Historical Society.

[16] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 89.

[17] New York Times July 16, 1876; OR 31:2:257–58.

[18] Society of the Army of the Cumberland, Society of the Army of the Cumberland: Twenty-eighth Reunion (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke, 1900), 80–81.

[19] Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant (hereafter Grant, Memoirs) (New York: Charles L. Webster, 1885–86), 2:78.

[20] Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant (hereafter Grant, Memoirs) (New York: Charles L. Webster, 1885–86), 2:79.

[21] Thomas Wood to Ulysses S. Grant, May 25, 1885, Grant Papers 10:15 Personal & Professional Correspondence, Library of Congress (LoC).

[22] OR 31:2:264.

[23] August Willich to Cincinnati Commercial, March 10, 1876, Ezra Ayres Carman Papers, New York Public Library.

[24] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 96; OR 31:2:281.

[25] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 90, 96.

[26] Sheridan OR 31:2:189; Philip H. Sheridan, Personal Memoirs of P.H. Sheridan, General United States Army (New York: Charles L. Webster, 1888), 1:319.

[27] Sheridan OR 31:2:190.

[28] Battles and Leaders 3:724.

[29] Battles and Leaders 3:724.

[30] OR 31:2:459.

[31] Grant, Memoirs 2:77–78.

[32] William F. Smith, “An Historical Sketch of the Military Operations around Chattanooga, Tennessee, September 22 to November 27, 1863,” Papers of the Military Historical Society of Massachusetts (Boston: Military Historical Society of Massachusetts, 1910) 8:216, 237.

[33] William Farrar Smith to Dennis Hart Mahan, December 7, 1863, William Farrar Smith Papers, LoC.

[34] Battles and Leaders 3:717.

[35] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 91.

[36] OR 31:2:508.

[37] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 101.

[38] Paul M. Angle, ed., Three years in the Army of the Cumberland: the Letters and Diary of Major James A. Connolly (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987) 150.

[39] Society of the Army of the Cumberland, Society of the Army of the Cumberland: Twenty-fourth Reunion (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke, 1894) 64.

[40] Grant, Memoirs 2:78.

[41] Grant, Memoirs 2:79–82.

[42] New York Times, July 16, 1876.

[43] Society of the Army of the Cumberland, Society of the Army of the Cumberland: Twenty-eighth Reunion (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke, 1900), 80–81; Edwin W. High, History of the Sixty-eighth Indiana Volunteer Infantry, 1862–1865 (S.l.: s.n., 1902), 150.

[44] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 87. Simpson referenced Dana and Wilson’s The life of Ulysses S. Grant. This uncritical work, written to promote Ulysses Grant’s 1868 election bid, contained many mistakes in his favor, such as falsely describing how Grant’s plan of operations at Chattanooga “was to attack the rebels on both flanks at the same time, and when they should be sufficiently shaken, to throw his whole army upon them,—and to finish the work with a single crushing blow.” Charles A. Dana and James H. Wilson, The Life of Ulysses S. Grant, General of the Armies of the United States (Springfield: Gordon Bill, 1868), 144.

[45] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 93.

[46] James Harrison Wilson to William Farrar Smith, September 20, 1886, James Harrison Wilson Papers, LoC.

[47] National Tribune, November 4, 1897.

[48] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 90.

[49] Battles and Leaders 3:725; OR 31:2:133; Gordon Granger to William S. Rosecrans, June 6, 1864, William S. Rosecrans Papers, UCLA; Thomas Wood, “The Battle of Missionary Ridge,” Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS) Ohio, 4:39, 41–42; National Tribune, November 4, 1897; New York Times, February 12, 1899.

[50] Battles and Leaders 3:725.

[51] Chicago Tribune, July 14, 1894.

[52] Sylvanus Cadwallader, Three Years with Grant: As Recalled by War Correspondent Sylvanus Cadwallader, Benjamin P. Thomas, ed. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1956), xv.

[53] Chicago Times, December 1, 1863.

[54] Cadwallader, Three Years with Grant, 150–51, 155.

[55] John E.P. Doyle to William S. Rosecrans, July 3, 1882, William S. Rosecrans Papers, UCLA. Wood, however, had left Orchard Knob by this time.

[56] New-York Tribune December 4, 1863; National Tribune, May 26, 1892.

[57] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 102.

[58] William W. Smith, “Holocaust Holiday: The Journal of a Strange Vacation to the War-torn South and a Visit with U.S. Grant, 1863,” Civil War Times Illustrated, vol. 18, no. 6 (October 1979), 36.

[59] Smith, “Holocaust Holiday, 36.

[60] OR 31:2:45.

[61] William Le Baron Jenney, “With Sherman and Grant from Memphis to Chattanooga: A Reminiscence,” MOLLUS, Illinois, 4:213–14.

[62] Ulysses S. Grant, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant (PUSG), John Y. Simon, ed. (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1967–2012), 3:134, 138.

[63] PUSG 5:78–79.

[64] Grant, Memoirs 2:88.

[65] OR 31:2:281.

[66] OR 31:2:264, 301.

[67] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 104.

[68] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 92, 94, 96, 97, 98, 99.

[69] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 87, 100; Adam Badeau, Military History of Ulysses S. Grant, from April, 1861, to April, 1865 (New York: D. Appleton, 1868–81), 1:508–9.

[70] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 91.

[71] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 86.

[72] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 90.

[73] Battles and Leaders 3:725.

[74] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 85–86. New York Herald, December 2, 1863.

[75] New York Herald December 2, 1863; New York Times, February 12, 1899.

[76] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 99; Sword, Mountains Touched with Fire, 264, 396.

[77] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 100; OR 31:2:68, 103.

[78] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 84, 94–96.

[79] Simpson, “What Happened on Orchard Knob?” 95. Simpson emphasized how much faith he put in Catton’s supposition, asking, “Why, then, had anyone ever thought otherwise?”

[80] Steven E. Woodworth and Charles D. Grear, eds. The Chattanooga Campaign (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2012), 3. Sam Davis Elliott and Ethan Rafuse, two other authors with articles in this volume, decided that Grant intended a diversion, as opposed to an ascent. In another book that Steven Woodworth edited, Mark Grimsley accurately summarized how Grant was “the apparent victor (although George H. Thomas was really more responsible for the Northern success).” Steven E. Woodworth, ed., The American Civil War: A Handbook of Literature and Research (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1996), 279.